︎ [Student] Housing is Health

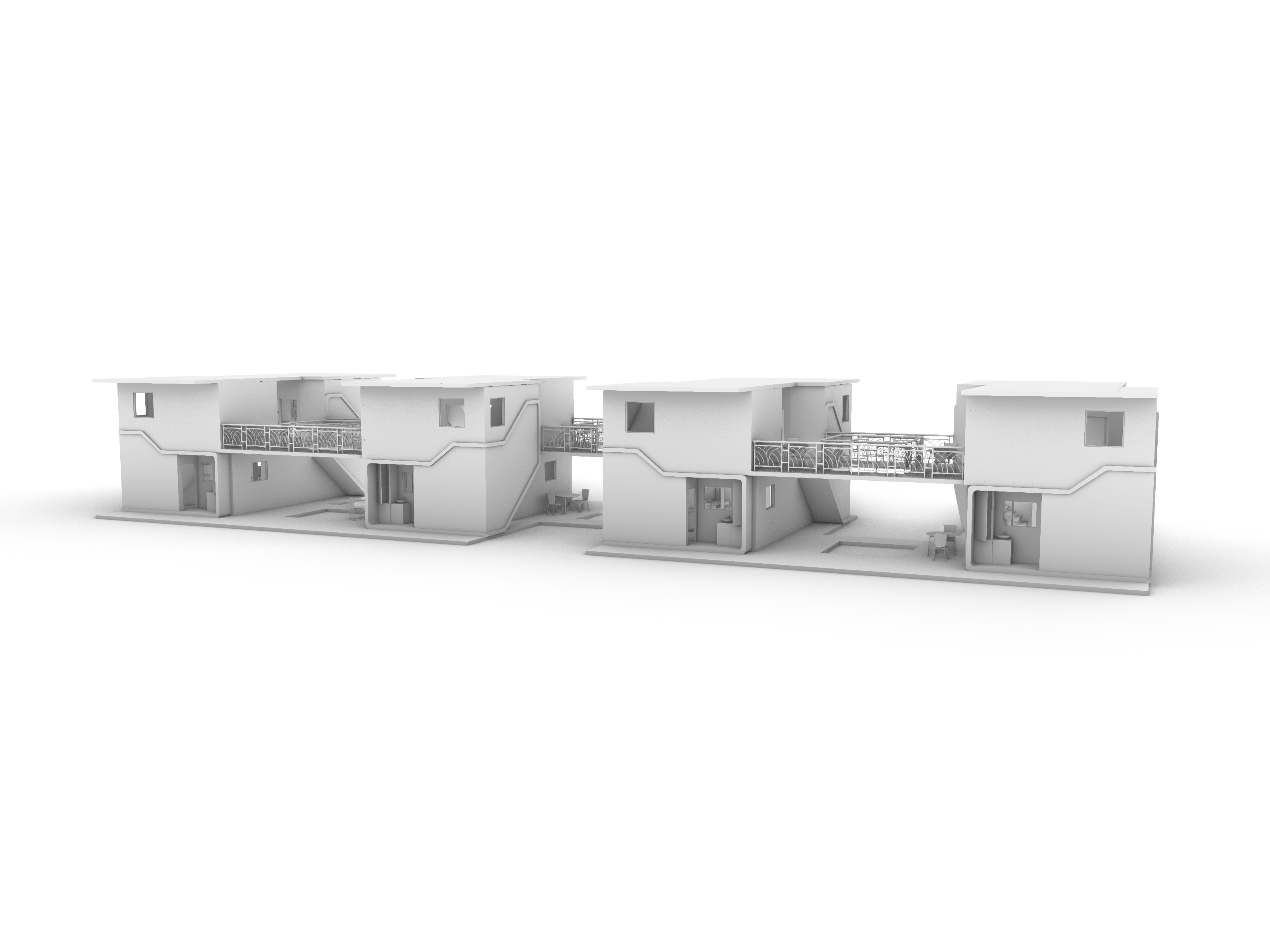

Strategies for healthier student housing, specifically as they relate to two bedroom apartments, using the existing Northwood IV student housing complex at the University of Michigan as an example.

By Noah Russin ︎

On campus housing is an essential part of college and university life. However, as a result of the pandemic, while vacancy rates are high, schools are developing strategies to combat the spread of disease.

This presentation focuses on design strategies schools can potentially use to create healthier student housing. One of the University of Michigan’s student housing options, Northwood IV, is used as an example to showcase these strategies, specifically as it relates to two-bedroom apartments.

The University of Michigan offers a variety of on-campus student housing ranging from one-bedroom apartments to four-bedroom suites. Northwood IV boasts the availability of a two-bedroom apartment equipped with a shared kitchen, shared bathroom, a study area, and a combined dining and living room (Michigan Housing).

College and university housing present an important question which design can help answer: How can students maintain health and wellbeing while sharing an apartment and apartment complex?

By Noah Russin, August 2020

Hypothesis: Each of the interventions introduced, using the University of Michigan’s existing Northwood IV student housing as an example, will allow for a healthier student population.

By Noah Russin, August 2020

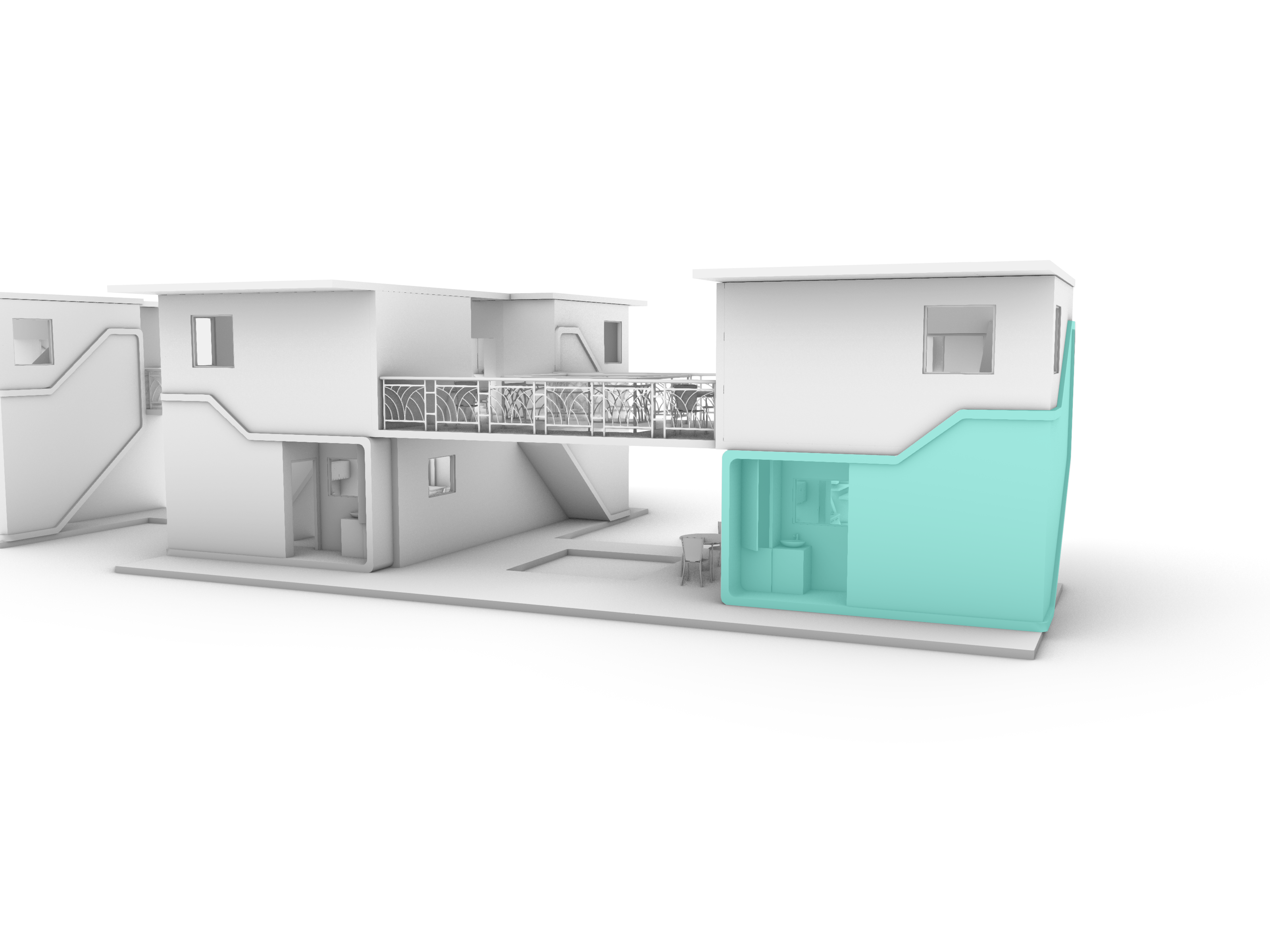

The first strategy for improving health safety in the University of Michigan’s student housing is to separate the massing of each apartment. Design should consider allowing for more distance between students upon approaching their units, therefore reducing the likelihood of transmission.

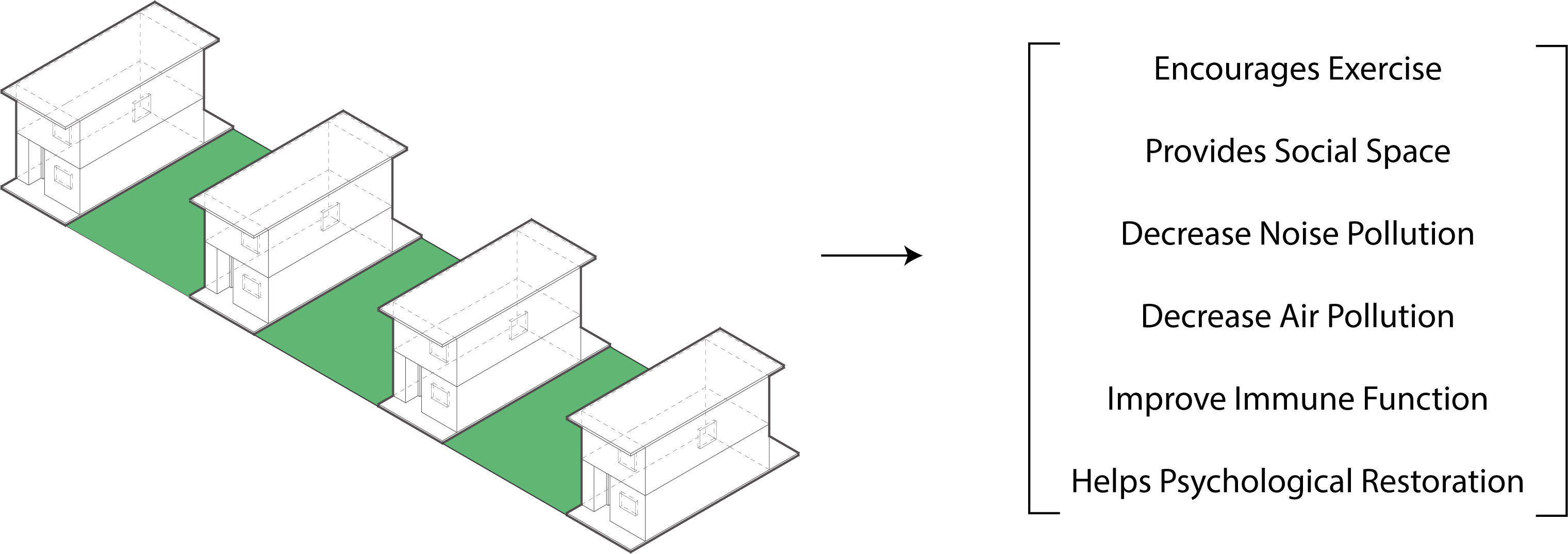

By separating the massing of each apartment, more green space can be introduced between apartments. According to Earth Observatory at NASA, “green space is good for mental health” (NASA). “It can encourage exercise, provide spaces for socializing, decrease noise and air pollution, and improve immune function by providing exposure to beneficial microbiota. It also can help with psychological restoration; that is, green space provides a respite for over-stimulated minds” (NASA). We all know how over-stimulating academic settings can be. Research from World Resources Institute found “urban trees in the United States could yield $25 million in savings just in air pollution related health care costs and lost workdays” (Thomson Rueters Foundation). These benefits are crucial when extrapolated to a campus setting. Students often find themselves over-worked and over-stressed and a simple solution to this is the introduction of more and better green spaces, especially close to where students live.

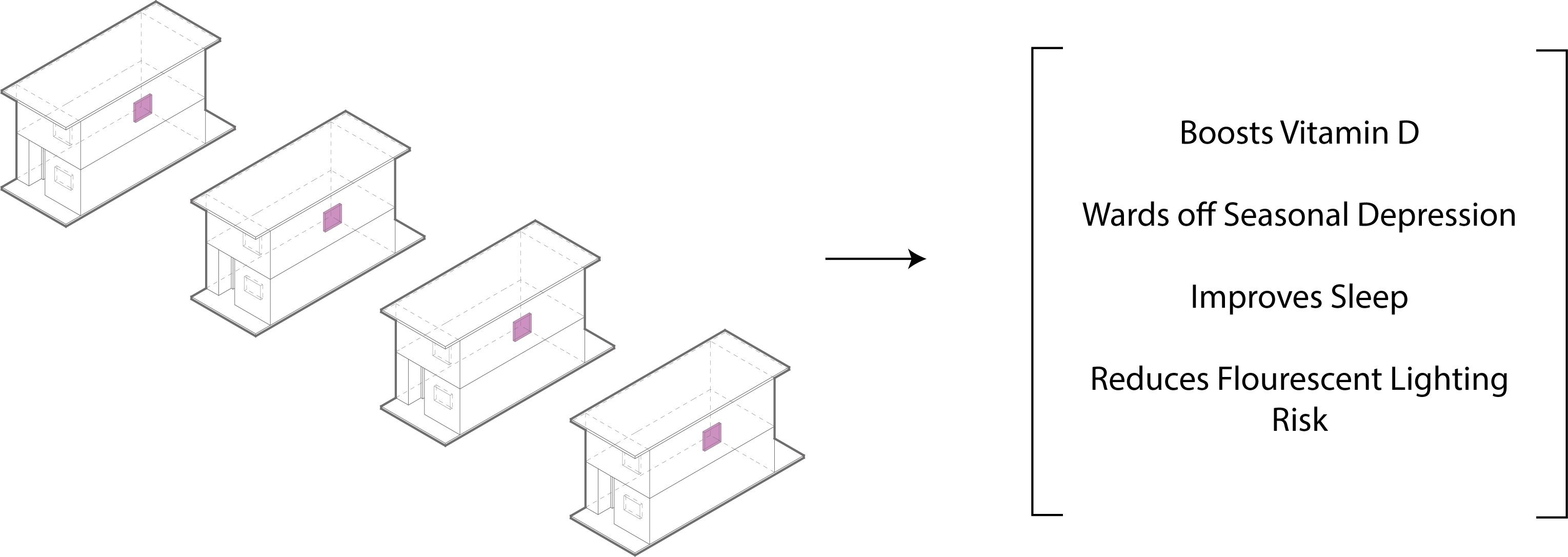

By separating the massing of each apartment, more windows can be introduced so that the full benefits of greater green space can be experienced. This can be accomplished because walls are no longer being shared by adjacent apartments. This also allows for more windows to be southern facing in order to consistently face the Sun in the northern hemisphere, allowing them to make the most of solar gain by letting natural light shine through while absorbing heat. According to Healthline, “natural light provides measurable health benefits by boosting vitamin D, warding off seasonal depression, improving sleep, and reducing the health risks associated with fluorescent lighting” (Garone).

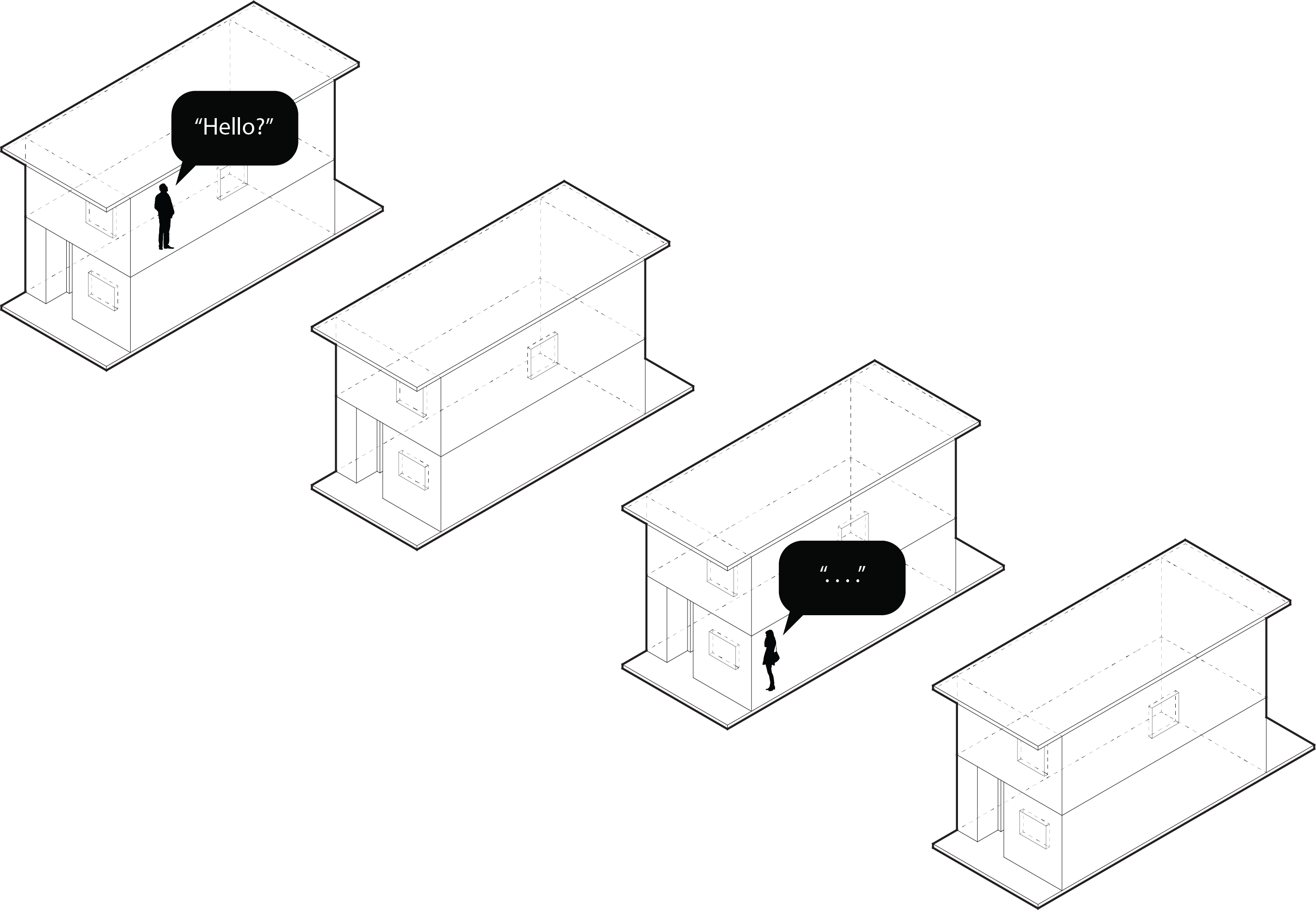

Since walls are no longer being shared by adjacent apartments, the risk of noisy neighbors is essentially eliminated. This is ideal for a university setting especially during a pandemic. It can be difficult to concentrate or converse via video conferencing with noisy neighbors. By separating the massing of the apartments, noise is significantly reduced.

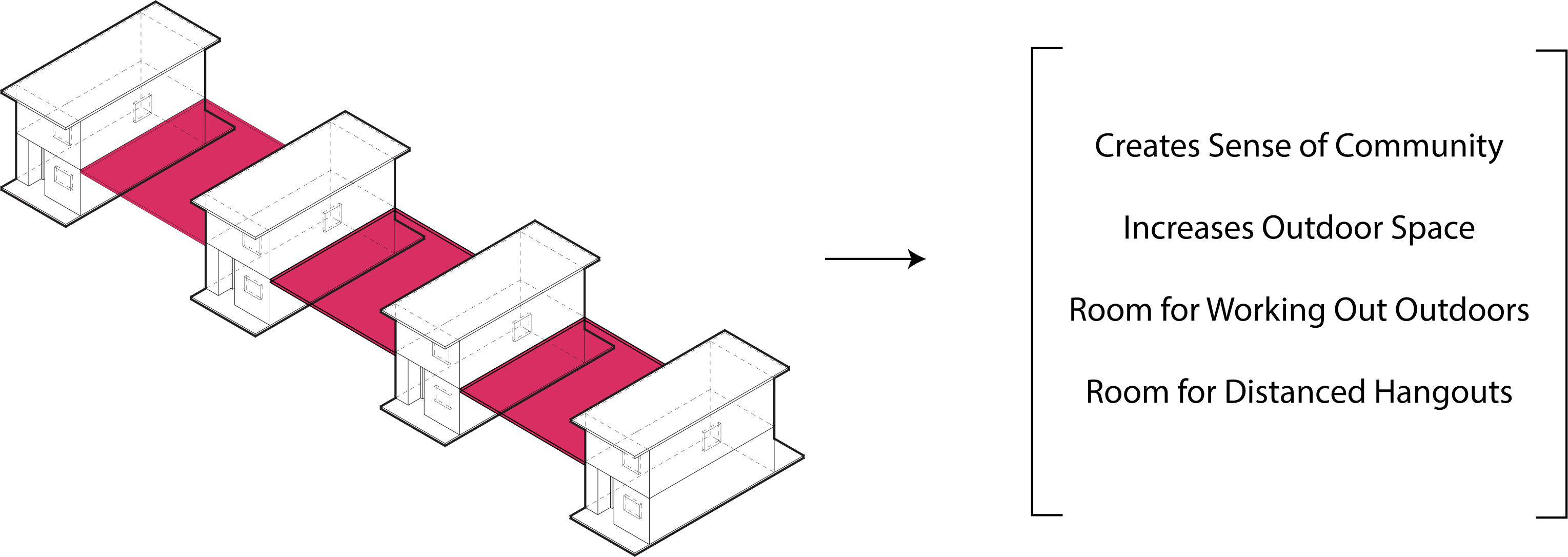

By separating the massing of each apartment, a feeling of community can be somewhat lost. By physically distancing apartments from each other, residents are also physically distanced. This can be beneficial in terms of reducing the risk of transmission but can be detrimental in terms of fostering social space and a sense of community. By connecting the second level balconies into one cohesive platform, a greater sense of community can be accomplished, while also increasing balcony and outdoor space for each resident. This provides space that can be used for working out, social hangouts both distanced and non-distanced, studying outdoors, and more. It also allows for neighbors to be more easily connected, which is not always the best thing. In order to separate the visual connection from a person’s bedroom to the balcony, no windows are adjacent to the balcony and the balcony is staggered to reflect the interior layout of the apartments.

Each of the interventions mentioned to this point reflect health measures between apartments but not within them. A student should not have to worry if their roommate is experiencing symptoms or has tested positive that the disease will automatically be transmitted to them. The layout of each apartment reflects this worry and introduces various interventions as means to combat this risk.

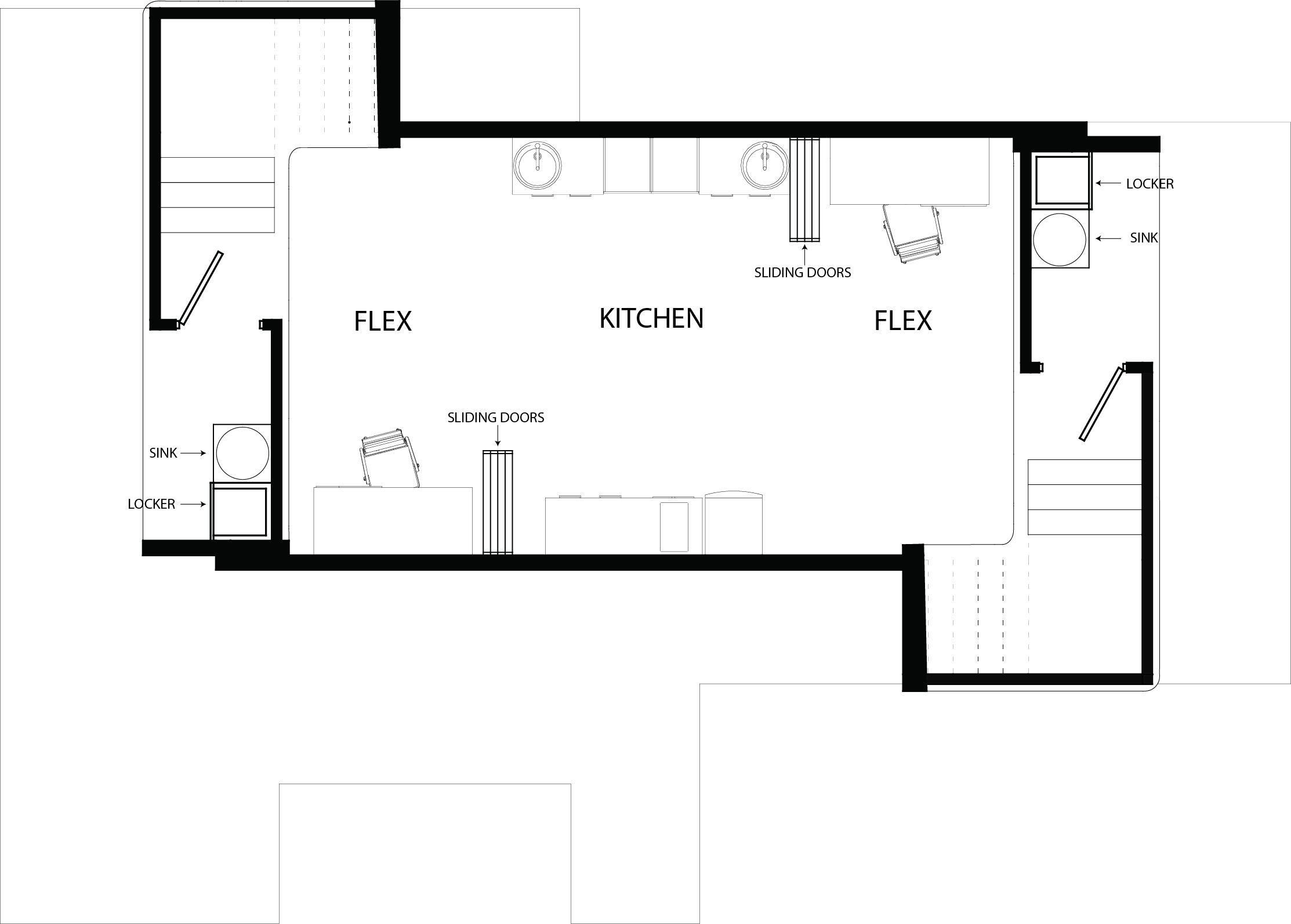

Upon approaching the two-bedroom units, the residents will notice that they each have their own entry way and circulation. This significantly reduces the possibility of transmission by physically separating high touch surfaces and shared air space which would otherwise exist if there was only one entryway and one set of stairs.

The threshold between outdoors and indoors becomes a particularly important tool in separating sanitized space from un-sanitized space. As opposed to just being a wall with a door for entry, the threshold should rather be utilized as a space that allows one to wipe down or wash away any fear of disease compromised materials. Adjacent to the front door for each resident, exists a small locker and a sink. This allows the student to place any potentially compromised materials such as a jacket, coat, sneakers, or other items which may have come into contact with the disease in the locker before entering the apartment. It also allows and emphasizes the importance of washing hands before entering the apartment. This space can also be utilized during times of health. The locker can used for extra storage and is a great place to keep an umbrella or an extra jacket for those especially cold days in Michigan.

Upon entering the apartment and within the threshold space also exists circulation for each resident to reach the second floor of the apartment. By creating a separate circulation space, residents do not have to worry about using the same air space or railing with a potentially sick roommate.

On the first level of each apartment exists two flex spaces, one for each resident, and a shared kitchen equipped with a stove oven, refrigerator, two sinks, and plenty of storage space.

The flex spaces provide a large enough area to be utilized in whatever way the student likes. This space can be used for schoolwork, working out indoors, dining, socializing and more. The two flex spaces are separated by the shared kitchen. Sliding glass panels allow each resident to close themselves off when they feel necessary. The glass panels can be closed off on either side of the kitchen so as to provide more flexibility and options when needed. These panels can be closed off if one roommate is sick or has tested positive for the disease. It can also be closed off when one student is trying to focus on work while the other cooks or has friends over. The panels provide a distancing measure while also retaining the importance of visual connectivity.

During times of pandemic, the first floor can be effective in separating a compromised roommate from a healthy one. The two residents can negotiate who has access to the kitchen and can choose to slide whichever of the two sets of panels makes the most sense. During times of health, the panels can be slid back into place and the first floor can be shared between the roommates.

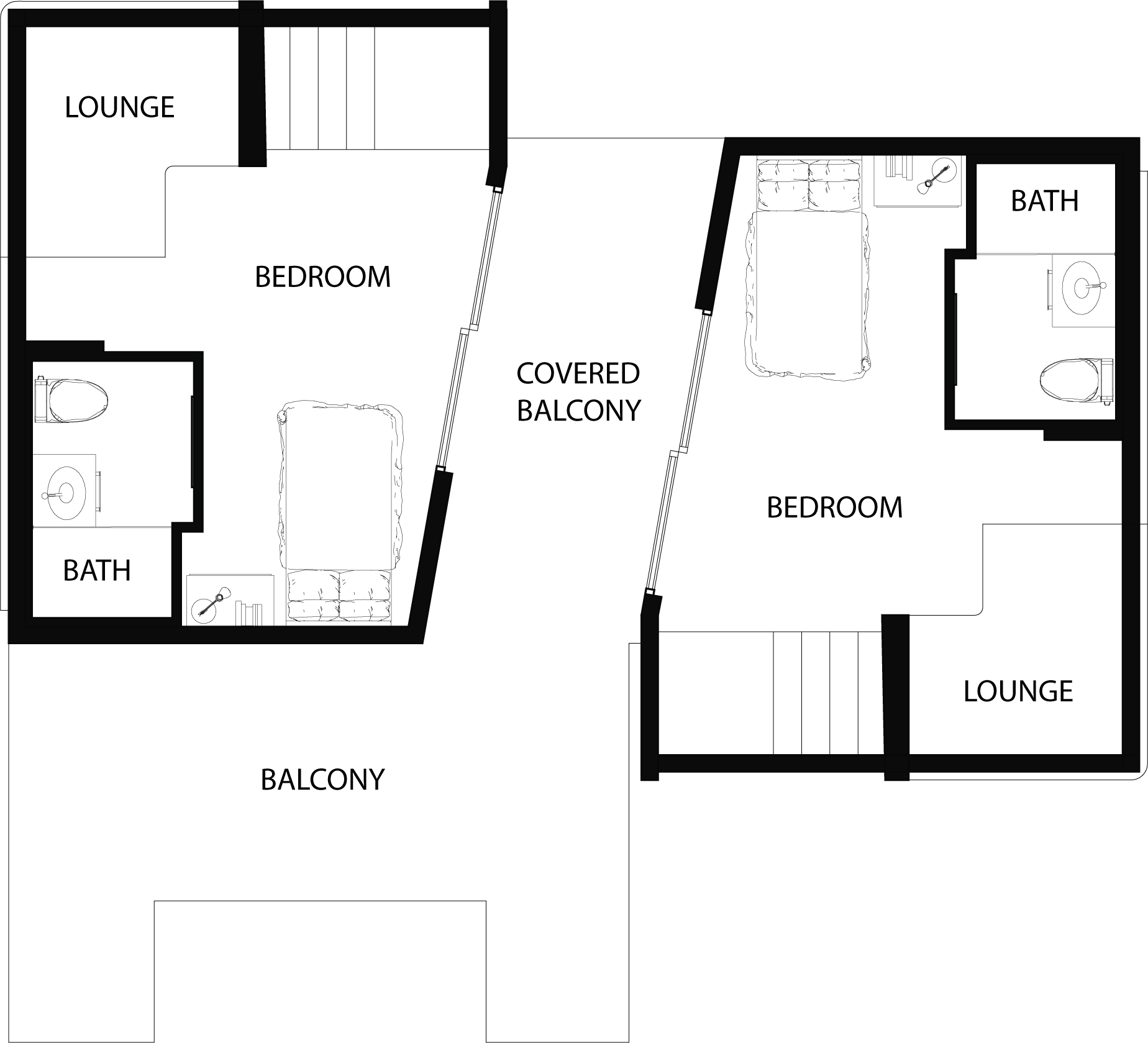

After ascending their respective stairs to the second floor, the resident will find themselves in their own bedroom. The second floor consists of two bedrooms, one for each resident, with an open but covered balcony space between them. The bedrooms come with their own bathroom, bed, and lounge area. Because each resident has their own bathroom, as opposed to a shared one, the risk associated with sharing bathroom space with a potentially sick roommate is eliminated.

The balcony space between the bedrooms allows for better ventilation of the whole space. Between the sliding glass doors and the operable windows, the apartment can be opened up to vent any compromised air particles thus reducing the risk of disease spreading amongst roommates.

Testing the Hypothesis

In order to test whether the hypothesis is correct or not, a study can be conducted to analyze students’ health and production before and after these strategies are implemented. This can be done through surveys as well as statistical analyses of the health of the student population. If health improves and students feel comfortable, safe, and productive in the new space that utilizes these strategies, then the hypothesis is correct.

The Bottom Line

Understandably, a college or university might be hesitant to apply these interventions. Most of these interventions imply an increase in cost in terms of construction. By separating the massing of the building, more walls need to be constructed. By introducing more windows, a larger balcony, more sinks, sliding glass panels, and a spatially larger design, construction costs will surely increase.

However, these costs can be mitigated when taking a holistic approach to university financing. Typically, in order for a college to pay for a new building or to renovate an existing building a combination of revenue, contingency savings, federal bonds and grants, state bonds and grants, public-private partnerships, or donors are used (Kroll).

A public-private partnership can potentially be utilized to deliver this project. A private developer is incentivized to complete this project because although the rents must be affordable, the occupancy rate will almost always be 100%. This means that all of the apartments will most likely be booked reducing the risk associated with financing the project. When considering what students will want in choosing housing, health safety will be at the front of everyone’s minds following this pandemic. This design clearly delivers that need which again shows the likelihood of a 100% occupancy rate. This reduction in risk and the partnership in and of itself reduces the costs.

Typically, a university will also hold a contingency fund. This fund is designed to be used when economic struggles are experienced. This pandemic presents the perfect reason for a university to utilize these savings in order to provide for the student population. When analyzing the cost benefit relationship of doing so a few issues should be considered. First, if a university does not provide the necessary health safety measures for on campus housing then it automatically will be competing with nearby residences as well as other schools who are introducing health safety measures. If the student population as a whole and the student population who choose to live on campus diminishes, the university will have a difficult time financially. The cost of constructing these interventions is significantly less when compared to the costs associated with losing a portion of the student population.

Schools also need to consider the health benefits of these interventions and their associated cost decreases. It is likely that due to these interventions the college or university will experience a healthier overall student population. This decreases the cost burden put on academic health institutes therefore reducing the net bottom line for the school. By providing a health safety intervened building, the school will likely experience savings in other areas of their financing, again reducing the overall cost associated with delivering this project.

︎

Works Cited

Alati, Danine. “These Are the 7 Requests Clients Will Make Post COVID-19.” Architectural Digest, 22 May 2020, www.architecturaldigest.com/story/these-are-the-7-features-clients-will-be-requesting-post-covid-19.

Chayka, Kyle, et al. “How the Coronavirus Will Reshape Architecture.” The New Yorker, 17 June 2020, www.newyorker.com/culture/dept-of-design/how-the-coronavirus-will-reshape-architecture.

Davies, Sophie. “Sliding Walls, Hideable Offices: How Pandemic Could Change Home Design.” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, 4 Aug. 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-global-homes/sliding-walls-hideable-offices-how-pandemic-could-change-home-design-idUSKCN2500FY.

Foundation, Thomson Reuters. “Sliding Walls: How Pandemic Could Change Home Design.” News.trust.org, 4 Aug. 2020, news.trust.org/item/20200804114129-f29h2/.

Garone, Sarah. “11 Things to Know About Natural Light and Your Health.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 3 Oct. 2018, www.healthline.com/health/natural-light-benefits.

“Green Space Is Good for Mental Health.” NASA, NASA, 2019, earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145305/green-space-is-good-for-mental-health.

Kroll, Karen. “Types of Funding for Construction Projects on Campus |.” University Business Magazine, 12 Nov. 2019, universitybusiness.com/capital-projects-5-ways-to-pay/.

Mackres, Eric. “Insights from Big Data on How COVID-19 Is Changing Society.” World Resources Institute, 22 July 2020, www.wri.org/blog/2020/05/insights-big-data-how-covid-19-changing-society.

“Northwood III.” Michigan Housing, 10 Aug. 2020, housing.umich.edu/residence-hall/northwood-iii/.

Ogundehin, Michelle. “‘In the Future Home, Form Will Follow Infection.’” Dezeen, 4 June 2020, www.dezeen.com/2020/06/04/future-home-form-follows-infection-coronavirus-michelle-ogundehin/.

“Risk Management Plan for Buildings.” The American Institute of Architects, 2020, www.aia.org/resources/6299432-risk-management-plan-for-buildings.