︎ Street Greening

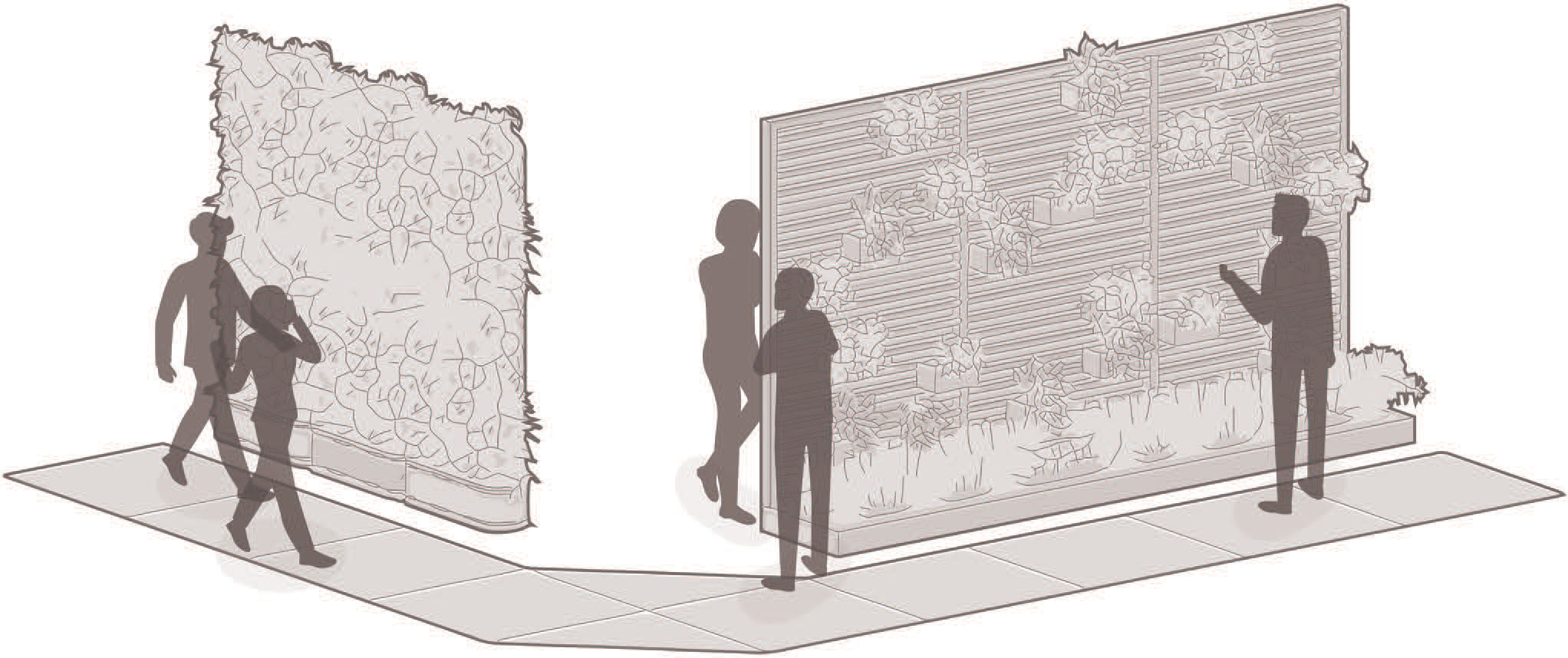

Re-envisioning the relationship of privacy and engagement through vertical planters, providing comfort to the residents, and interaction for the passerby

By Scott Crandall ︎

Hypothesis

Despite the comfort found in the environment of Ann Arbor, Michigan, there’s still a degree of visual and auditory distraction caused by local traffic (both vehicular and pedestrian). The main roadways leading into Ann Arbor are hot spots for both of these kinds of ”pollution”, a problem that is only exacerbated during local events (such as sports or festivals). This makes life a little less comfortable for the residents stationed along these high-traffic corridors.

Despite the comfort found in the environment of Ann Arbor, Michigan, there’s still a degree of visual and auditory distraction caused by local traffic (both vehicular and pedestrian). The main roadways leading into Ann Arbor are hot spots for both of these kinds of ”pollution”, a problem that is only exacerbated during local events (such as sports or festivals). This makes life a little less comfortable for the residents stationed along these high-traffic corridors.

- Why?

Noise pollution and visual disturbances will be decreased leading to reduced stress and irritation to the residents.

- How?

Installation of vertical planters

- What?

Privacy, comfort, and increased interaction using street greening.

- So What?

This may encourage residents to engage more in outdoor activities, increasing opportunities for community interaction and physical activity.

The design of street greening.

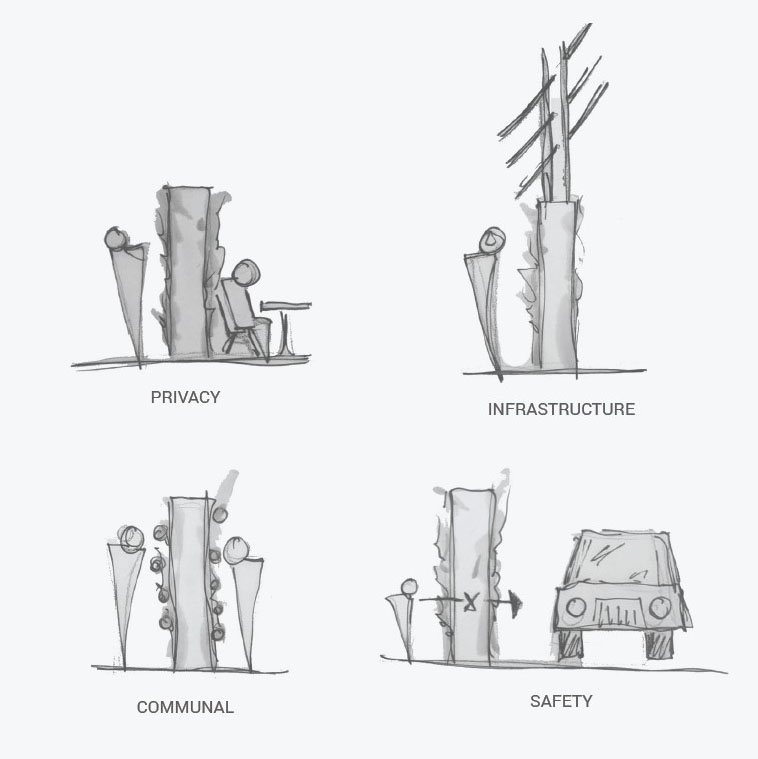

Design to Outcomes

By proposing a network of infrastructural vertical planters, we can both mitigate the pollution caused by the activities of these corridors, providing privacy and solace to the residents, as well as providing opportunities for curated engagement between both the residents and the chance pedestrians. Ann Arbor is already considered a botanical haven due to the ratio of plant-to-hardscape it maintains, and this would only benefit that status. Beyond this, there’s a variety of tertiary benefits that could be obtained through such a consideration.

︎

Works Cited

1. “Walker's Paradise.” n.d. Walk Score. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.walkscore.com/score/ann arbor, michigan.

2. MapEsri, HERE, Garmin, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GISuser communityBureau of Transportation Statistics, VOLPECONUS https://maps.bts.dot.gov/arcgis/apps/webappviewer/index.htmlid=a303ff5924c9474790464cc0e9d5c9fb

3. Holzman, David C. 2014. “Fighting Noise Pollution: A Public Health Strategy.” Environmental Health Perspectives 122 (2). https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.122-a58.

4. A. Can, L. Leclercq, J. Lelong, D. Bottledoren. Traffic noise spectrum analysis: dynamic modeling vs. experimental observations. Applied Acoustics, Elsevier, 2010, vol71, n8, p764-70. ffhal-00506615.

5. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al., editors. Neuroscience. 2nd edition. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2001. The Audible Spectrum. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10924/

6. “What Is the Decibel Scale?” n.d. What Is the Decibel Scale | Soundstop.co.uk. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.soundstop.co.uk/decibel-scale.

7. Fan, Yang & Zhiyi, Bao & Zhu, Zhujun & Jiani, Liu. (2010). The Investigation of Noise Attenuation by Plants and the Corresponding Noise-Reducing Spectrum. Journal of environmental health. 72. 8-15.