︎ Community Care Cruiser

Mobilizing Healthcare to Meet YOU!The Mobile Healthcare Unit aims to bridge healthcare gaps by offering adaptable, community-oriented services in both rural and urban areas. Through partnerships, geospatial analysis, and culturally tailored initiatives, it provides essential health education, screenings, and social support, while integrating green spaces to promote well-being and foster personal connections within communities.

By Nana Temple ︎ , Marianna Godfrey ︎, Chloe Zhang ︎, Kristina Marchand ︎

Why

Nearly 30 million Americans still lack health insurance. Because of this coverage gap, individuals are unable to afford their co-pays, prescriptions, or gas to go to the doctor’s, leaving them without access to ample healthcare. Additionally, more people refuse to go to the doctor because of schedule, fear, or location, leaving many without vital check-ups.

How

Leveraging the power of GIS and RVO’s Healthgrades software, these advanced tools transform underutilized spaces into areas where the Care Cruiser can park and the inflatable can be set up for patients. By using these software tools, we can pinpoint locations in neighborhoods that lack sufficient healthcare access, identify underutilized community central spaces, and locate nearby health professionals. This efficient process ensures that our mobile clinic is always where it’s needed most, maximizing its impact on the community’s health.

Using GIS, RVO’s Healthgrades, and Public Health data, locating sites in need of primary care and bringing in-person care to these places. This model can be scaled up and used to combat the needs from climate change and disaster relief

The proposal is a mobile clinic that provides easy access to primary care and adapts to the needs of both urban and rural sites. It seamlessly integrates with the local area and providers to deliver the best care to the community it serves. The truck, acting as a vessel for the inflatable module, offers enclosed spaces with seating, interactive displays, and green spaces. This innovative design makes visiting the doctor engaging and barrier-free, ensuring that healthcare is not a burden but a convenience for the community.

So What

Primary care is vital for well-being and preventing debilitating diseases, which primary care accounts for through routine check-ups. While numerous barriers of location, lack of insurance, and fear cause people not to go to the doctor, this cruiser provides accessible care within a community, promoting well-being and increasing access to primary care for communities in need.

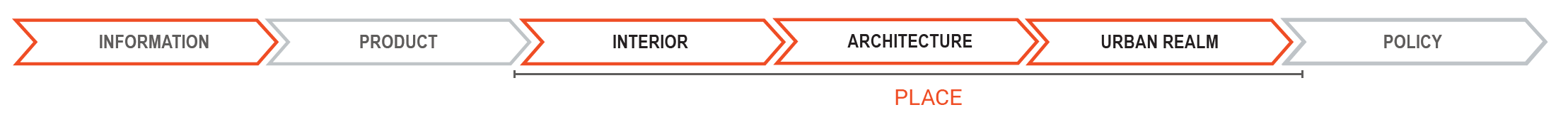

Design To Outcomes

In-person Care

The Cruiser provides a unique opportunity to provide in-person care rather than relying on virtual appointments. By identifying places to park, technology furthers in-person interaction and connection instead of replacing it.

Collaboration within the Community

By identifying local healthcare providers using Healthgrades and teaming up with local community organizations, businesses, and leaders, the Cruiser helps strengthen the connections and bonds within the community itself.

Welcoming Environment

Instead of a sterile, enclosed doctor’s office, the Cruiser comes to a familiar location within a community. The inflatables include interactive displays, green space, and flexible seating, providing a fun and low-stress place for primary care.

Accessible Care

The Cruiser is more than just a healthcare service. It’s a lifeline for those who may have limited access to primary care. Whether you’re in a rural or urban area, facing financial constraints, or simply feeling anxious about healthcare, the Cruiser is here to bridge the gap., bringing healthcare to communities and aiding them in disease prevention and well-being

A proposed layout for the inflatable set up in a park in Detroit with comfortable waiting room, private modular inflatable check-up rooms and room for outdoor activities and health education

︎︎︎Two Page Report

︎︎︎Miro Board

︎

Works Cited

2. Loehrke, Jack, and George Petras. "Coronavirus Hospitals in the Field: How the Army Corps of Engineers Fights COVID-19 with Tents." USA Today, 17 Apr. 2020.

3. Della Vella, Domenico, and Mariana F. Rayo. "The Final Inch: What Pop-Up COVID Testing Tells Us About Community Engagement." Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care, vol. 11, no. 1, 2022, pp. 76-81. DOI:10.1177/2327857922111015

5. Roeper, Brooke, et al. "Mobile Integrated Healthcare Intervention and Impact Analysis with a Medicare Advantage Population." Population Health Management, vol. 21, no. 5, 2018, pp. 349-56.

6. Oriol, Nancy E., et al. "Calculating the Return on Investment of Mobile Healthcare." BMC Medicine, vol. 7, no. 27, 2009. DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-7-27

7. Patrick Drake, Jennifer Tolbert. "How Many Uninsured Are in the Coverage Gap and How Many Could Be Eligible if All States Adopted the Medicaid Expansion?" KFF, 26 Feb. 2024. Link

8. Ulrich, Roger S., et al. "Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments." Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 11, no. 3, 1991, pp. 201-230. DOI:10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

9. Tribble, Sarah Jane. "A Mobile Clinic Parked at a Dollar General? It Says a Lot About Rural Health Care." NPR, 5 Oct. 2023.

10. Nanda, Upali, et al. "Clinic 20xx: Designing for an Ever-Changing Present." CADRE.

11. World Health Organization. "Primary Health Care." World Health Organization.

12. Yu, Sylvia W.Y., et al. "The Scope and Impact of Mobile Health Clinics in the United States: A Literature Review." International Journal for Equity in Health, vol. 16, no. 178, 2017. DOI:10.1186/s12939-017-0671-2