︎ THRESHOLD: Designing the spaces in between, where health decisions take place.

Everyday life is shaped not just by the rooms we occupy, but by the moment of transition between them. These guide how we interact not just with space but with our own health. In The Healing Threshold, we turn our attention to the role these moments can play in supporting daily health. By reimagining domestic thresholds as sensory and spatial cues for healthy decision-making, everyday movements can become intuitive and dignified forms of self-management—turning moments of burden into moments of balance.

By Catherine Henebery ︎ , Caleb Lee︎, Pruthvi Shah ︎, & Gino Zunzunegui ︎

This project is grounded in the lived reality of Ladonna

Thomas, a 68-year-old woman managing Type 2 diabetes,

limited mobility after a below-knee amputation, and mild cognitive decline that affects her memory and confidence. Her

husband, Melvin, carries the parallel weight of caregiving,

navigating fatigue, isolation, and the constant vigilance her

routine requires. Together, their experience shows that diabetes is

not only a medical condition but a daily reality that shapes

memory, mobility, and the need for sustained support. Ladonna and Melvin live in a small manufactured home outside Marshall, North Carolina, along a rural highway with no sidewalks, no safe outdoor areas, and a grocery store four miles away. With limited transportation for clinic visits, the home becomes her primary site of care where nearly all health decisions and challenges must be managed.

Inside, narrow corridors, cluttered counters, and improvised storage shape how Ladonna eats, moves, and remembers what to do next. Tasks such as checking her CGM, drinking water, or preparing insulin often depend on Melvin’s help. Her health is guided less by intention and more by the physical and cognitive cues embedded in the spaces she moves through.

Her home already functions as a healthcare hub. This project asks how it might become a supportive one.

memory, mobility, and the need for sustained support. Ladonna and Melvin live in a small manufactured home outside Marshall, North Carolina, along a rural highway with no sidewalks, no safe outdoor areas, and a grocery store four miles away. With limited transportation for clinic visits, the home becomes her primary site of care where nearly all health decisions and challenges must be managed.

Inside, narrow corridors, cluttered counters, and improvised storage shape how Ladonna eats, moves, and remembers what to do next. Tasks such as checking her CGM, drinking water, or preparing insulin often depend on Melvin’s help. Her health is guided less by intention and more by the physical and cognitive cues embedded in the spaces she moves through.

Her home already functions as a healthcare hub. This project asks how it might become a supportive one.

Why

For Ladonna, every care action happens in a different corner of the home, demanding a level of coordination and energy she cannot always sustain. Thresholds that should support smooth transitions instead become points of friction, where narrow passages, poor lighting, and visual clutter require constant cognitive effort. Simple tasks—checking a CGM alert, responding to an insulin reminder, preparing a meal—accumulate into dozens of fragmented micro-decisions that drain focus and

confidence.

Images taken from FDA Idea Lab’s Lilypad VR Experience

How

To address these breakdowns, we began by mapping Ladonna’s daily routine—her movements, energy levels, and the moments where she pauses, hesitates, or loses confidence. This process revealed which transitions consistently created friction and how they disrupted her care. We then identified the key health-related thresholds in her home, translating each friction point into an opportunity for flow, clarity, or pause. Related care actions such as eating, monitoring, and dosing were reorganized into visible, accessible clusters that reduce cognitive strain. Spatial prompts—light, texture,

adjacency—were aligned with daily transitions to support readiness and recall, helping transform scattered tasks into smoother, more coherent routines.

Graphic drawn by Catherine Henebery

What

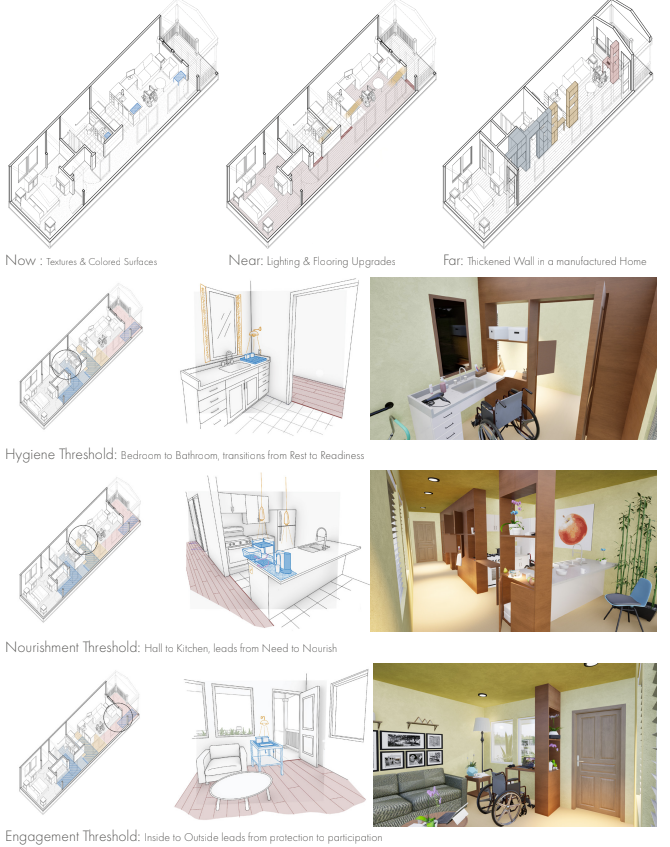

Our interventions follow a Now / Near / Far framework that accounts for both time and cost. Now focuses on the immediate, low-cost actions Ladonna and Melvin can take to support her diabetes management without altering the home. Near introduces modest interior interventions that can be added gradually—improvements that strengthen her routines but are not invasive, expensive, or time-intensive. Far envisions a redesigned model of manufactured home that leverages its flexible, simple structure to incorporate an intentional architectural intervention, transforming the interior into a long-term, supportive environment for care.

The Now phase focuses on improvements Ladonna and Melvin can implement immediately with minimal cost or disruption. Once the key thresholds are defined (bedroom to bathroom for hygiene, hall to kitchen for nourishment, and inside to outside for engagement) small “care zones” are created at each transition.

Designated counters near the bathroom door, at the kitchen entrance, and by the front door provide clear places to keep essential itemsvisible and organized, supporting both spatial and cognitive thresholds. Tactile mats, storage containers, raised surfaces, and color coding increase accessibility by stabilizing objects and signaling where actions should occur. These low-tech, low-cost interventions help Ladonna maintain her routines more reliably by placing the right tools in the right transitional moments.

The Near phase introduces moderately scaled interior interventions that are feasible over time and do not require altering the structure of the home. The carpet is replaced with hardwood to improve wheelchair mobility and reduce physical strain. At each threshold, subtle transition strips act as sensory reminders, prompting Ladonna to hydrate, eat, or complete her hygiene routine as she moves through the home.

Lighting is also added at each care zone, illuminating the items she relies on while providing a gentle visual cue to complete her next step. These enhancements build on the Now phase by making the home more navigable, legible, and supportive of consistent, independent routines.

Far

In the Far phase, the manufactured home is reconceived as an architectural system that embeds care directly into its structure. A continuous thickened wall spans the length of the home, transforming each threshold into a supportive environment that guides Ladonna through her day with clarity and stability. This wall combines open and closed storage, keeping essential items visible for memory support while concealing others to reduce the emotional burden of constant reminders. It also creates designated zones for both Ladonna and Melvin, restoring autonomy and easing the shared weight of care.

Within the Hygiene Threshold, the thickened wall provides a built-in CGM surface at the transition between bedroom and bathroom, turning an easily forgotten task into a natural, spatially prompted moment. Inside, removing the under-sink cabinet creates full wheelchair clearance, and a dual-access cabinet lets her reach hygiene items from either the hallway or the bathroom without making a tight turn.

In the Nourishment Threshold, the wall reorganizes the hall-to-kitchen transition. Open shelving places healthier items at clear, reachable heights, and a pull-out table creates a safe, seated prep surface for simple meals or medication—reducing her reliance on Melvin.

At the Engagement Threshold, the thickened wall restructures the entry sequence to reduce hesitation and encourage connection. Organized storage for keys, water, and papers, along with a fold-out telehealth surface, prepares her for both leaving home and participating in remote care. Aligned views to an exterior planterprovides a daily visual cue to step outside, turning the threshold into a point of possibility rather

than a barrier. Integrated throughout the wall, tactile materials and programmed lighting act as sensory cues that prompt care at the right moments. Rather than adding equipment onto the home, the Far phase uses the inherent flexibility of manufactured housing to reshape the interior itself into a long-term, adaptive tool for wellbeing. Through this architectural rethinking, thresholds no longer interrupt her routines—they sustain them.

VR Environment created by students based on Lilypad Experience

So What

Working through thresholds reframes Ladonna’s home from a collection of rooms, to a sequence of critical decision points where care either advances or falls apart. By redesigning these transitions, the thickened wall turns everyday movement into moments of support, clarity, and self-management. This approach does not medicalize the home or add intrusive equipment—instead, it activates what already exists, transforming thresholds into quiet, powerful supports for independence, rhythm, and dignity. By centering thresholds as sites of care, the project demonstrates how small architectural shifts can reorganize the entire experience of health at home. When design reduces friction, it restores agency. When transitions are clear and supportive, safety and consistency emerge naturally from daily motion. Through this work, the home regains its role as a partner in care, offering Ladonna and Melvin confidence rather than burden. It also offers a model for health-inclusive domestic design, where wellbeing is sustained not by devices, but by the architecture itself.

Design To Outcomes

The Healing Threshold demonstrates how architectural design can directly support diabetes care by transforming the transitions between rooms into structured moments of guidance, recall, and stability. Instead of treating the home as a set of isolated spaces, the project focuses on thresholds—those brief in-between moments where Ladonna’s care routines often falter. By redesigning these transitions, the home becomes a system that gently prompts, organizes, and reinforces daily health actions.

The design unfolds through a phased Now / Near / Far framework. Now introduces low-cost, immediately implementable care zones at key thresholds, using tactile mats, raised surfaces, and organized storage to make glucose checks, hydration, and medication easier to perform. Near strengthens routine through interior improvements such as hardwood flooring for mobility, sensory transition strips for recall, and targeted lightingthat highlights essential care items. Far reimagines the home with a continuous thickened wall that integrates open and closed storage, fold-out work surfaces, and embedded sensory cues—turning the architecture itself into a long-term partner in diabetes management. Across phases, the design transforms thresholds into supportive, intuitive anchors that restore clarity, autonomy, and dignity in daily life.

Links to Follow:

︎︎︎Report

︎︎︎Miro Board

︎

Works Cited

2. Hollands, G. J., Shemilt, I., Marteau, T. M., Jebb, S. A., Lewis, H. B., Wei, Y., Higgins, J. P. T., & Ogilvie, D. (2013). Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: Towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health, 13, 1218. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3890582/

3. Kirkman, M. S., et al. (2023). Self-management of diabetes is a dynamic process of learning and behavioral adaptation. Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11096776/

4. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2023, December 14). Type 2 diabetes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20351193

5. Pallasmaa, J. (2012). The eyes of the skin: Architecture and the senses (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

6. Simmel, G. (1994). Bridge and door. Theory, Culture & Society, 11(1), 5–10.

7. Turner, V. (1982). From ritual to theatre: The human seriousness of play. Performing Arts Journal Publications.

8. Ulrich, R. S., et al. (2008). A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design.

9. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1(3), 61–125. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21161908/

10. van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage (M. B. Vizedom & G. L. Caffee, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1909)

11. Woodward, A., Walters, K., Davies, N., Nimmons, D., Protheroe, J., Chew-Graham, C. A., Stevenson, F.,& Armstrong, M. (2024). Barriers and facilitators of self-management of diabetes amongst people experiencing socioeconomic deprivation: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Health Expectations, 27(3), e14070. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.14070

12. American Diabetes Association. Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes.org. https://diabetes.org/about-diabetes/type-2